There's something special about stumbling onto the rare photo of a young Black artist at play before they became a household name. I think of Maya Angelou's time as a dancer at a string of San Francisco night clubs before and after touring with the European review of Porgy and Bess. Images from this part of her life feel special, in part, because there are so few of them. Is it naïve of me to imagine the archive, before social media and rampant consumption from the press, as a space for greater ownership of the Black image?

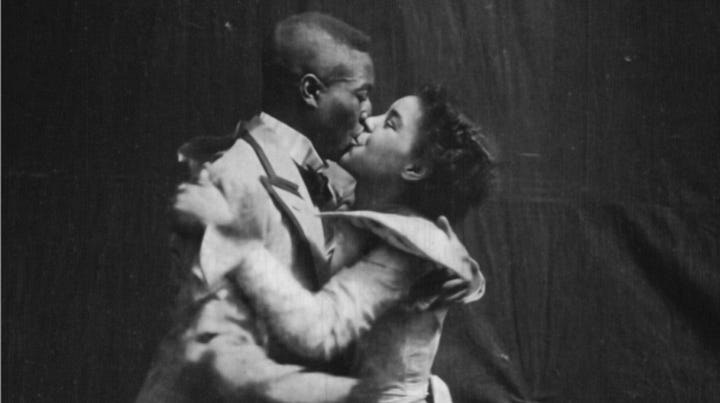

The 1898 silent film, Something Good - Negro Kiss, holds a similar sense of nostalgia and importance for modern viewers but its actors never owned the footage and they had little creative control over the way they were presented. Gertie Brown and Saint Suttle were well-known vaudeville performers of the time and members of The Rag-Time Four who helped popularize the cakewalk. But their Negro Kiss was actually directed and produced by William Selig - a white man who had previously dabbled in minstrel shows. It's unlikely that his interests aligned with anything resembling liberation of the Black image. Which explains why the film was left to languish for over a century until discovered at an obscure yard sale. In this context, the rarity of a piece of Black artistry does not necessarily signal intentionality or care.

Instead, the je ne sais quoi appeal of these artifacts has as much to do with a very purposeful reclamation of their meaning in the present as any impromptu disregard for the external gaze in the past.

Multidisciplinary choreographer, T. Lang, and Grammy award-winning jazz musician, Kebbi Willams, beautifully negotiated this balance with their recent production of Black Kiss (Still Good), a celebratory homage to Brown and Suttle. Billed as a midnight show on the occasion of Williams’ 50th birthday, the January 8th performance transported its lucky audience to a time and place worthy of any turn-of-the-century quartet (or countless smoke-filled arthouse clubs of the 1920s-60s, for that matter). Of course, the venue was not just any nameless night club but Gallery 992, Williams’ own Atlanta event space. Lang’s artistic direction made use of the brick-walled, warehouse aesthetics by placing the seating along the periphery, with Williams and his ten-piece band centered on the open floor, and five paired couples engaged in an hour long ‘kiss’ discreetly off to one side of the band along a back wall.

This arrangement allowed for an intimacy that would go on throughout the night in brief exchanges that transcended purely romantic or physical displays of affection. It also served to shield the couples from prying eyes in the face of the bold choice to cast them all as nude models throughout the piece. At several moments I found myself craning my neck, trying to catch a glimpse of the performers across a sea of heavy brass and percussive instrumentation blocking my view, despite what I thought had been a front row seat. Among the standing-room-only crowd, this misdirection felt like a purposeful choice. Clothed only in flesh-toned thongs and androgynous bowl-cut wigs, the sparce costuming allowed Lang’s prolonged gestural choreography to shine through.

The band and performers all faced inward, engaged in a shared tenderness. At the same time, a lone videographer repeatedly circled the slim moat of walkable space between the band at center and the audience lining the walls. Spectacle may not have been the intent but a very deliberate and protective documentation of this exhibitionist moment seemed clearly vital to the cause. So much of the evening’s proceedings felt designed to highlight Black love and celebration as the key to emancipating Black art within the canon.

My thoughts here return to Maya Angelou, this time to the infamous Chester Higgins photo of her dancing with Amiri Baraka over a cosmogram containing the ashes of Langston Hughes at the Schomburg Center in New York. The sheer magnitude of Black culture bound up in this group of artists engaged in mutual admiration is at the heart, the very essence, of what was equally palpable in the air during Black Kiss (Still Good).

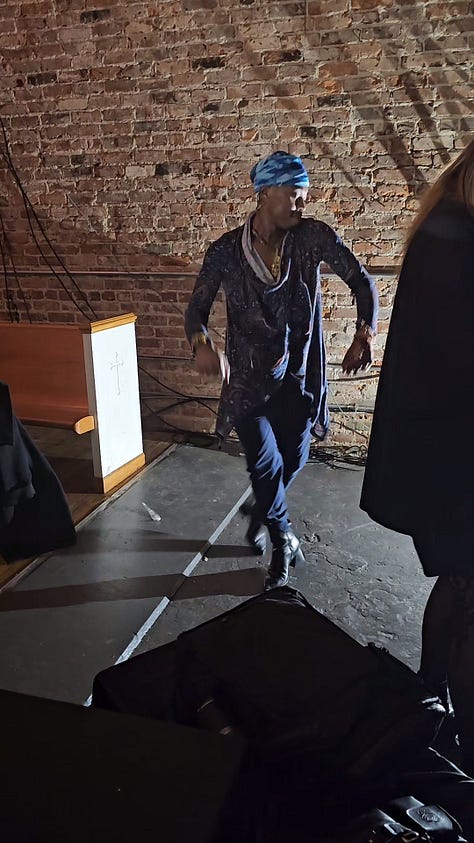

A saxophone begins us before moving through several waves of Williams’ signature free jazz composition. The entire band are shirtless in black jeans that give off an air of funk swagger and surprising vulnerability to match the exposed nature of each nude couple. I notice myself identifying the musicians by a combination of their limited headwear and chosen instrument. Tenor thick glasses. Cymbals, horn, cowbell. Teased out ‘fro, black and white skully, locs. They pulse and crash, driving sound toward crescendo after crescendo of noise, static, scatter, scratch, bliss, maelstrom, wind, whisper, silence. Finally, Kebbi on flute.

Among the couples piled in front and on top of a small table, several are on the floor, limbs tangled. Awkward yet unhurried. No rough rush. A single languorous collection of bodies. A disembodied hand caressing soft flesh from navel to abdomen and up a ticklish ribcage. The wigs and spare costuming also extend this performance outside the limited constraints of gender or a purely heterosexual interpretation. In the handful of photos that Lang shared from her January 6th auditions, they all appeared to be in cis-het pairings. Like the band, however, what they're wearing accomplishes as much as what they are not. Appearances are no longer clear.

Time disappears into flute, wind, sound. After a while, I spy a soft-spoken phrase from Williams to Black-and-White Knit Skully. Thick and Third take turns positioning themselves, the wires, and their instruments to share a single stanchion. This moment requires specific sheet music. The threesome make it work and the band goes on as limbs stretch step over each other in the tight container of center stage. Facing inward, there's a separate sonic kiss happening in this space between bare chested men. Pillow talk gives way to passion. Heavy. Frenetic. Everything happening at once. Where are we? Who's moving? Tambourine.

There's a woman playing the tambourine to my left. I briefly wonder where she came from. Another member of the band? No. We've entered a state of evolutionary chaos. The kiss has taken over. When I glance up, two halves of a disparate whole stand on the table across a small island of band equipment. Arms raised, backs arched, they strike statuesque poses.

A handful of guests have already slipped out of the venue. Time having left the building, there's no way to be sure how late it is. Their reasons for leaving are equally underwater. Of course, the most obvious possibility hangs in the air like cloudy bar smoke. An hour long staged ‘pre-kiss’ may not have been exciting enough. For those who got lost in the promise of a 60-minute more passionate or risqué kiss, they completely missed the point. I do not envy them.

Thank you all for coming tonight. My name is Kebbi Williams… and it’s my birthday.1

For those of us who made it to this celebratory end, we may have just witnessed a moment of live Black art that will go down as the start of several young careers and a convening of creative camaraderie among two already shining stars.

From the moment Williams escorted his collaborator, Lang, to her proffered seat at the back of house, before taking his own place among the band to start the show, there was a clear exchange of quiet care among all parties. Williams offering a final glance that seemed to ask, You good? Lang smiling and nodding. Good.

Black Kiss (Still Good) - January 8th 2024. Gallery 992 - Ralph David Abernathy Blvd.

Choreographer/Director: T. Lang

Composer: Kebbi Williams.

Models: Abigail Bryan; Amanda Egbu; Claire; Jaylen Clay; Jonathan Bryant; Knowledge; A. Raheim White; Roman Enerchi; Sherí Lillie; Ugo Agoruah.

Musicians: Brandon Stephens; Dallas Dawson; Darren Stanley; Eric Fontaine; Eric Porter; Marquinn Mason; Preston Stephens; T.J. Merit.

Closing video is a post-show clip of Kebbi Williams playing the flute, 2024.